FRONT ROW, Left to Right

Robert Long, Cal Guthrie, Jerry Southard

CENTER ROW, Left to Right

John Burt, Jim Gregory, Bill Magee, Ken Calotis, Clay Choo, Gary Hagen

BACK ROW, Left to Right

Robin Hunt, Howard Johnson, Rich Burns (Top), Ed De La Vergne, Dave Bateman, Tim Yost

Robert Long, Cal Guthrie, Jerry Southard

CENTER ROW, Left to Right

John Burt, Jim Gregory, Bill Magee, Ken Calotis, Clay Choo, Gary Hagen

BACK ROW, Left to Right

Robin Hunt, Howard Johnson, Rich Burns (Top), Ed De La Vergne, Dave Bateman, Tim Yost

Note: To pause the video, right click on it, and click on the "play" option

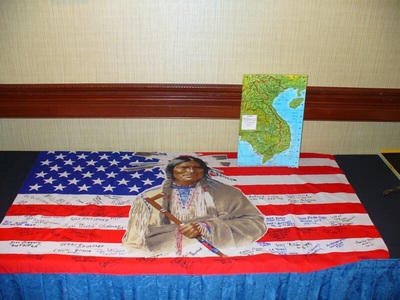

In Honor of John Seebeth, the Dust Off medic who was wounded in August of 1969

21 year-old Warrant Officer William Statt (bottom left) was considered to be one of the best Dustoff pilots because he possessed a magical ability of man and machine operating as one. All of the pilots were good, but Statt was a true hot-dogger who boldly got his bird in and out of some perilous situations. He was piloting on the day that John Seebeth was shot. His skilled maneuvering helped to save John's life.To save time when every precious minute counted, Statt performed a landing he had only read about in the books.

JOHN N. SEEBETH, Specialist Five, US Army, is awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for heroism while participating in aerial flight. evidenced by voluntary actions above and beyond the call of duty in the Republic of Vietnam; Specialist Five Seebeth distinguished himself by exceptionally valorous actions during the period 20 August 1969 through 22 August 1969 while serving as flight medic aboard an unarmed medical evacuation helicopter during rescue missions in the Hiep Duc Valley south of DaNang. At times without helicopter gunship cover or any other mode of air support, Specialist Seebeth and fellow crewmen undertook the dangerous task of evacuating the wounded and dead soldiers of the 196th Infantry Brigade, 7th Marine. and 5th ARVN regimental units from the midst of a raging battle involving major elements of the 2nd North Vietnamese Army Regiment and 1st Viet Cong Regiment. While supervising the loading of patients, often while receiving enemy fire, Specialist Seebeth is also commended for performing life saving medical treatment during the flight back to the 23rd Medical Battalion aid station located at LZ Baldy. On what turned out to be Seebeth’s final mission, the Dustoff crew responded to an urgent request to evacuate a severely wounded American soldier on August 22, 1969. The unarmed Medivac helicopter undertook the mission and entered the fire-fight without benefit of gunship escort. The Dustoff chopper and crew came under light automatic weapons fire which left Specialist Seebeth with a gunshot wound to the neck. The professional competence -- both medical and aerial skill -- and unwavering devotion to duty displayed by Specialist Seebeth reflect great credit upon himself and the United States Army.

The following article is written by Captain Robert B. Robeson, a pilot with the 236th Medical Detachment, Helicopter Ambulance and is excerpted from the May, 1983, edition of Soldier of Fortune magazine.

DUSTOFF!: "God Go With Us"

He trudged through the ankle-deep sand at the 95th Evacuation Hospital in Da Nang, Vietnam, displaying the smiling face I would learn to appreciate so much in the next few months. He was short, wiry, and he saluted even though his flight helmet was still on - visor up and intercom cord trailing out behind him like some dangling reptile.

Grabbing my overloaded duffel bag and effortlessly slinging it over a shoulder, he directed me toward the idling helicopter on the pad 50 yards away. It was my first glimpse of Specialist Five John N. Seebeth.

It was mid-July 1969. War would now be a reality for me, but Seebeth -- at 21-- had already seen it all. I wondered, later, if he'd ever really been young or if, like so many others I would get to know in Vietnam, he had been born old and experienced in the ways of death and life. Although the next month and a half would irretrievably alter our lives, I will never forget his smile at that first meeting -- and it was always there whether we were involved in good and hard times. I knew Seebeth was a good man for a bad medevac, but I knew little else about this grinning, gung-ho medic until it was really too late.

Our crew was assigned to field stand-by duty at LZ Baldy, about 25 miles south of Da Nang. Further south, Americal Division units had been engaged with an entire North Vietnamese Army (NVA) Division and we began flying 12 to 13 hours a day picking up their dead and wounded. During those 2 1/2 days, our DUSTOFF crew was forged into a team that worked under the worst conditions to save lives in combat.

I remember lying on my back on a dusty bunk during a brief lull in the action the second day, and talking to Seebeth across the hooch. A high-pitched voice and animated conversation were his trademarks and I smiled as he drew me a picture with hands that had saved many lives. This time the words had a serious note -- probably because we knew our odds were getting worse. He spoke rapidly and I listened and nodded as he talked. He brought up the possibility of our being shot down.

"Well, Sir" he said, "if we go down you can sure count on one thing." "What's that?" "That I won't leave you alone out there. Especially if you're hurt. If I have to die, I want to go trying to help someone or trying to protect my buddies."

At the moment it sounded a bit too dramatic, even though we'd already taken a number of "hits" the morning before in our first aircraft. I had been locked into my shoulder harness when a round entered behind my seat and broke the unlocking device.

But even in combat you don't really think the worst will ever happen. You see it all day but it's always someone else -- never you. We talked for a few minutes more until another mission being called in ended our discussion.

It was another insecure landing zone, under heavy small-arms fire. Normally, we'd try to get gunships to accompany us, but none were available because of the heavy action in the area. The ground troops had also radio-relayed to the aid station that the patient would be dead unless we got there immediately. Although we were unarmed, we agreed to go alone and try to sneak in as we'd done so many times before.

This mission was for a seriously wounded American. He waited for us in a valley that we'd gone into 10 to 15 times before. We had received fire on almost every attempt.

I remember looking down as we approached the area. It appeared calm and untroubled from 2,000 feet but inside I knew danger was waiting down there. Even Seebeth's usual "God go with us", spoken softly into his intercom before every approach, seemed different. The crew chief said later that he held up crossed fingers as he said it. He'd never done that before. Maybe intuition warned him.

Diving down from 2,000 feet, we spun quickly toward the yellow swirl of smoke in a tiny clearing. But all of our maneuvering was to no avail because we had to drop straight down into a "hover-hole" barely wider than our blades. We began taking hits before we touched the ground.

As our skids made contact, the entire jungle exploded with enemy fire. We were encircled. As they threw the wounded man aboard, holes popped in the chopper's skin as if by magic.

I turned to Seebeth to see if he was inside when a short burst of automatic fire blew open his neck. I yelled for the crewchief to assist him as we attempted to climb out of the ambush. The fire continued and knocked out all of our radios but one. Somehow we climbed and limped toward home. I turned in my seat and told Seebeth, "We'll get you back. You'll be all right." I doubted it since there was a ragged hole where his throat had been. He just shrugged his shoulders and instructed the crewchief, via hand motions, how to put the IV into his arm. Then he monitored its flow and kept his own airway clear of the blood that was quickly filling his lungs.

With great difficulty we flew the aircraft back and landed safely. A litter team was waiting for us but Seebeth pointed to the other patient, pushed them away, and ran 70 yards to the aid station- unassisted. As a medic, he knew the severity of his injuries and was well aware that seconds saved meant life.

I ran in behind him and marveled as he jumped up on an open litter used for examinations. He waved for the doctors to start working - doctors who had worked with him on other patients only hours before.

He kept mouthing the words, "I can't breathe", as they began a tracheotomy to get air to his lungs. There was no time for pain-killers -- they just started cutting. Seebeth was fighting to live and began kicking his feet in anger at his body's failure. I held his feet and tried to ease the fears we all had.

He looked at me. His lips moved silently: "I can't breathe", and big tears began to run down his cheeks -- mingling with the mucus and blood that covered him and everyone nearby. He suffered bravely until he passed out.

After surgery, Seebeth began to respond and was judged capable of being evacuated from the war zone for further surgery. I went to see him a number of times, between missions, at the evacuation hospital but he was always unconscious so I just stood by the bed feeling inadequate, watching the heaving chest and the tubes running in and out of his body.

I wished then that the whole world could have seen him bring three Americans back to life in one day after they had been placed aboard our aircraft apparently dead. Mouth-to-mouth breathing and closed heart massage, which he could do simultaneously, gave them another chance to live. Seebeth would do anything to save another human.

Days later, Seebeth was taken by helicopter to DaNang Air Force Base for evacuation. The crew that flew him over told us that as they took his litter from our ship to the waiting ambulance, Seebeth raised two fingers to form a "V" and then he raised his other hand. In it he waved our unit patch -- a patch that exhorted "Strive To Save Lives."

They said he was smiling through the blankets and tubes. The two pilots had to look away; they were all crying, Seebeth included. Even in combat there is time for love to grow, and we all loved Seebeth for what he was - the best medic we'd ever seen.

He had lost his larynx but not his spirit. He always gave more of himself than was required. He kept going because he believed that human life was the most important thing. I'll always remember those words before every approach, "God go with us."

Seebeth left his mark on the thousands he treated but he knew and respected the inevitability of death. He took his wounds the same way: fighting, but humble. His memory will always be with me - watered by tears and warmed by the smiles of yesterday. His words so long ago were prophetic- the memory of John Seebeth, of his courage and humanity, will never leave me alone. Seebeth was wounded in August 1969.

"Some men see things as they are and say, why? I dream things that never were and say, why not?" - Robert Kennedy.

DUSTOFF!: "God Go With Us"

He trudged through the ankle-deep sand at the 95th Evacuation Hospital in Da Nang, Vietnam, displaying the smiling face I would learn to appreciate so much in the next few months. He was short, wiry, and he saluted even though his flight helmet was still on - visor up and intercom cord trailing out behind him like some dangling reptile.

Grabbing my overloaded duffel bag and effortlessly slinging it over a shoulder, he directed me toward the idling helicopter on the pad 50 yards away. It was my first glimpse of Specialist Five John N. Seebeth.

It was mid-July 1969. War would now be a reality for me, but Seebeth -- at 21-- had already seen it all. I wondered, later, if he'd ever really been young or if, like so many others I would get to know in Vietnam, he had been born old and experienced in the ways of death and life. Although the next month and a half would irretrievably alter our lives, I will never forget his smile at that first meeting -- and it was always there whether we were involved in good and hard times. I knew Seebeth was a good man for a bad medevac, but I knew little else about this grinning, gung-ho medic until it was really too late.

Our crew was assigned to field stand-by duty at LZ Baldy, about 25 miles south of Da Nang. Further south, Americal Division units had been engaged with an entire North Vietnamese Army (NVA) Division and we began flying 12 to 13 hours a day picking up their dead and wounded. During those 2 1/2 days, our DUSTOFF crew was forged into a team that worked under the worst conditions to save lives in combat.

I remember lying on my back on a dusty bunk during a brief lull in the action the second day, and talking to Seebeth across the hooch. A high-pitched voice and animated conversation were his trademarks and I smiled as he drew me a picture with hands that had saved many lives. This time the words had a serious note -- probably because we knew our odds were getting worse. He spoke rapidly and I listened and nodded as he talked. He brought up the possibility of our being shot down.

"Well, Sir" he said, "if we go down you can sure count on one thing." "What's that?" "That I won't leave you alone out there. Especially if you're hurt. If I have to die, I want to go trying to help someone or trying to protect my buddies."

At the moment it sounded a bit too dramatic, even though we'd already taken a number of "hits" the morning before in our first aircraft. I had been locked into my shoulder harness when a round entered behind my seat and broke the unlocking device.

But even in combat you don't really think the worst will ever happen. You see it all day but it's always someone else -- never you. We talked for a few minutes more until another mission being called in ended our discussion.

It was another insecure landing zone, under heavy small-arms fire. Normally, we'd try to get gunships to accompany us, but none were available because of the heavy action in the area. The ground troops had also radio-relayed to the aid station that the patient would be dead unless we got there immediately. Although we were unarmed, we agreed to go alone and try to sneak in as we'd done so many times before.

This mission was for a seriously wounded American. He waited for us in a valley that we'd gone into 10 to 15 times before. We had received fire on almost every attempt.

I remember looking down as we approached the area. It appeared calm and untroubled from 2,000 feet but inside I knew danger was waiting down there. Even Seebeth's usual "God go with us", spoken softly into his intercom before every approach, seemed different. The crew chief said later that he held up crossed fingers as he said it. He'd never done that before. Maybe intuition warned him.

Diving down from 2,000 feet, we spun quickly toward the yellow swirl of smoke in a tiny clearing. But all of our maneuvering was to no avail because we had to drop straight down into a "hover-hole" barely wider than our blades. We began taking hits before we touched the ground.

As our skids made contact, the entire jungle exploded with enemy fire. We were encircled. As they threw the wounded man aboard, holes popped in the chopper's skin as if by magic.

I turned to Seebeth to see if he was inside when a short burst of automatic fire blew open his neck. I yelled for the crewchief to assist him as we attempted to climb out of the ambush. The fire continued and knocked out all of our radios but one. Somehow we climbed and limped toward home. I turned in my seat and told Seebeth, "We'll get you back. You'll be all right." I doubted it since there was a ragged hole where his throat had been. He just shrugged his shoulders and instructed the crewchief, via hand motions, how to put the IV into his arm. Then he monitored its flow and kept his own airway clear of the blood that was quickly filling his lungs.

With great difficulty we flew the aircraft back and landed safely. A litter team was waiting for us but Seebeth pointed to the other patient, pushed them away, and ran 70 yards to the aid station- unassisted. As a medic, he knew the severity of his injuries and was well aware that seconds saved meant life.

I ran in behind him and marveled as he jumped up on an open litter used for examinations. He waved for the doctors to start working - doctors who had worked with him on other patients only hours before.

He kept mouthing the words, "I can't breathe", as they began a tracheotomy to get air to his lungs. There was no time for pain-killers -- they just started cutting. Seebeth was fighting to live and began kicking his feet in anger at his body's failure. I held his feet and tried to ease the fears we all had.

He looked at me. His lips moved silently: "I can't breathe", and big tears began to run down his cheeks -- mingling with the mucus and blood that covered him and everyone nearby. He suffered bravely until he passed out.

After surgery, Seebeth began to respond and was judged capable of being evacuated from the war zone for further surgery. I went to see him a number of times, between missions, at the evacuation hospital but he was always unconscious so I just stood by the bed feeling inadequate, watching the heaving chest and the tubes running in and out of his body.

I wished then that the whole world could have seen him bring three Americans back to life in one day after they had been placed aboard our aircraft apparently dead. Mouth-to-mouth breathing and closed heart massage, which he could do simultaneously, gave them another chance to live. Seebeth would do anything to save another human.

Days later, Seebeth was taken by helicopter to DaNang Air Force Base for evacuation. The crew that flew him over told us that as they took his litter from our ship to the waiting ambulance, Seebeth raised two fingers to form a "V" and then he raised his other hand. In it he waved our unit patch -- a patch that exhorted "Strive To Save Lives."

They said he was smiling through the blankets and tubes. The two pilots had to look away; they were all crying, Seebeth included. Even in combat there is time for love to grow, and we all loved Seebeth for what he was - the best medic we'd ever seen.

He had lost his larynx but not his spirit. He always gave more of himself than was required. He kept going because he believed that human life was the most important thing. I'll always remember those words before every approach, "God go with us."

Seebeth left his mark on the thousands he treated but he knew and respected the inevitability of death. He took his wounds the same way: fighting, but humble. His memory will always be with me - watered by tears and warmed by the smiles of yesterday. His words so long ago were prophetic- the memory of John Seebeth, of his courage and humanity, will never leave me alone. Seebeth was wounded in August 1969.

"Some men see things as they are and say, why? I dream things that never were and say, why not?" - Robert Kennedy.

In Dedication to Ralph Freemen

Ralph Freemen was a crew chief with the 236th Med Det. Richard Claywell was with him when he was shot 6 times in January of 1971. Ralph was hit in the chicken plate 3 times, once in the arm, one in the hip and one in the face. Richard said they almost lost him. The pilot and co-pilot were also wounded. The ship had 26 entry points.